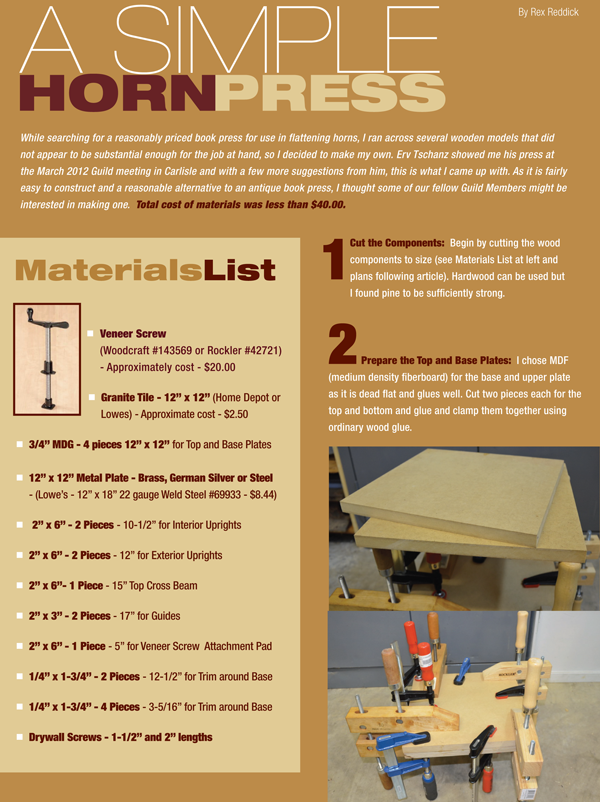

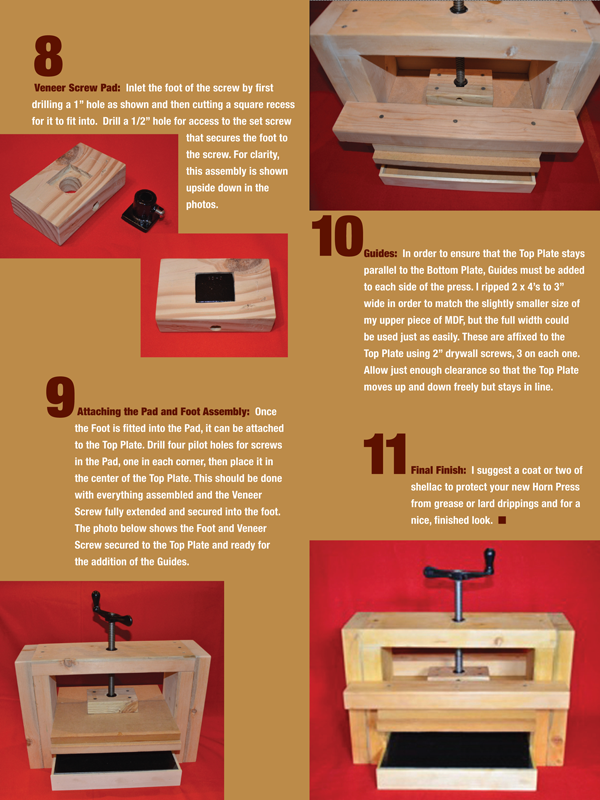

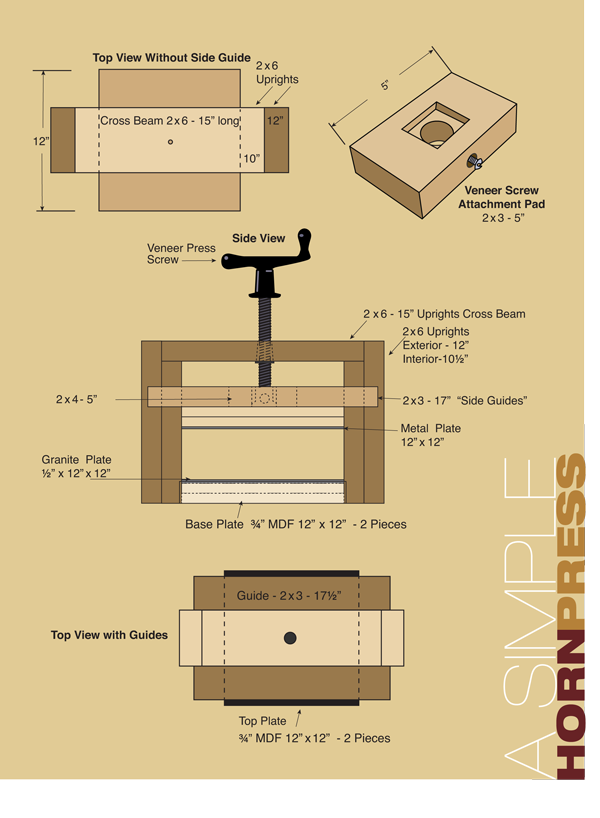

A Simple Horn Press by Rex Reddick

February 12, 2014 by Bill Carter

Filed under Articles from the Archives

This is a reprint from the Summer 2-13 issue of The Horn Book– A Simple Horn Press by Rex Reddick. While it may not be an oldie, it certainly is a goodie! -wec

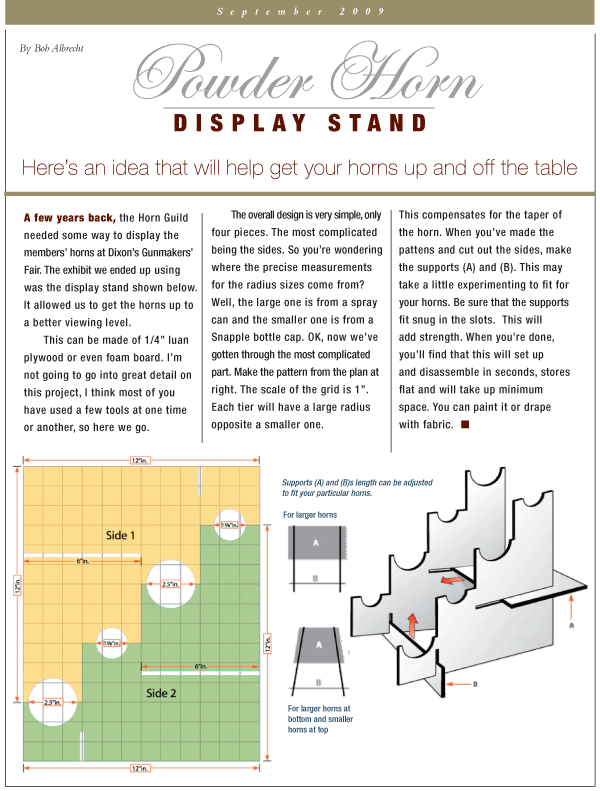

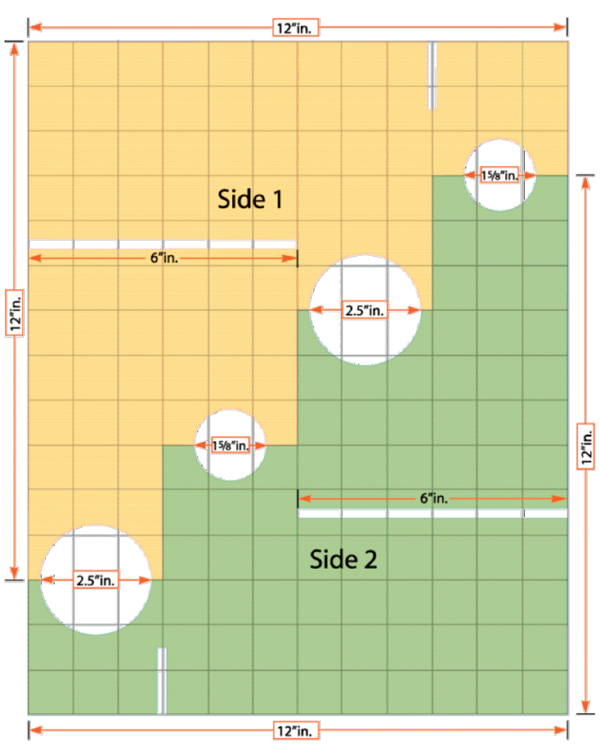

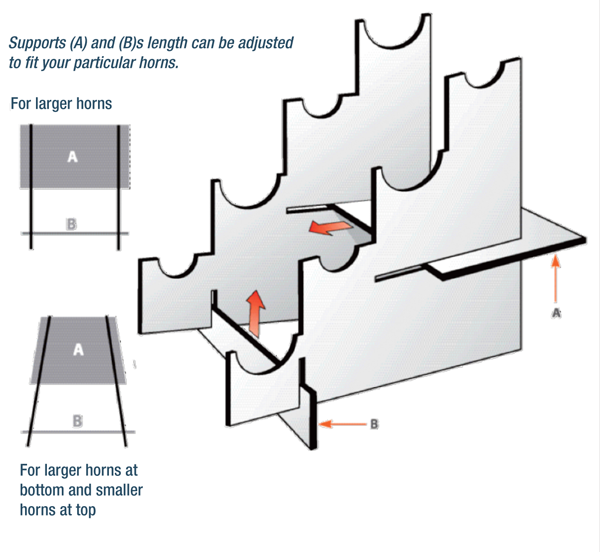

Build This Multi-horn Display Stand

April 11, 2013 by Bill Carter

Filed under Articles from the Archives

This is a repost of the Powder Horn Display Stand article from the September 2009 issue of The Horn Book. The website had a small issue that necessitated the repost. About the article: You will see this display stand in use at numerous events. I appreciate Bob Albrecht writing such a concise article on how to build this simple stand.

-WEC

The Question of Imported Horns

September 26, 2011 by Bill Carter

Filed under Articles from the Archives

The following article by Byron Smith was first published in the September 1999 issue of The Horn Book. It gives some excellent insights into the horn trade which I think you will enjoy.

– Bill Carter, Editor and Journeyman Horner

The Question of Imported Horns

By Byron C. Smith

In the 26 July 1759 Pennsylvania Gazette, an advertisement appeared which announced that a diverse quantity of goods had been imported “in the last Vessels from Bristol and London.” The announcement went on to say that they would be “sold wholesale or retail, at BLANCH WHITE’S Upholstery Warehouse, the Crown and Cushion, in Front Street, near the London Coffee House, Philadelphia.” Among the listed items are things that you would expect to see in a shop called “the Crown and Cushion,” such as “Upholsterers buckrams, furniture checks, erminettas,” as well as sundry other goods related to the textile trade. It is among the listings of hardware goods that we begin to see the things you would not expect to find in an “Upholstery Warehouse.” Among the “pullies, cranks and wire” we find “brass mounted swords,” and “fence pan gun locks.” Just before a listing for “steel mounted swords gilt with gold,” the ad mentions “powder horns and flasks.”

It is this reference to horns and flasks that we will address herein. My purpose in writing this article is to raise questions and the appearance and prevalence of imported powder horns. I also wish to touch on the evidence for specialization in the field of horn work and the implications this has on our understanding of the horn trade. It should be no surprise that horn powder flasks were being imported from Europe where they were being manufactured cheaply and efficiently. Indeed, considering the manufacturing power of Britain during the third quarter of the 18th century, it should not astonish us that powder horns were being imported from Britain in 1759. Obviously there were horns being made professionally in Philadelphia at the time. Nevertheless, during the years I have been studying the subject I have not heard much discussion of the role of these imported horns would have played in the American market. In short, we should be asking what did these horns look like and how many of them are out there, mislabeled as professionally made American horns?

Since 1759 was a peak year during the French and Indian War, one would expect that many goods with military value were being imported into America. In fact, the same advertisement closes with an addendum which includes listings for “Drums and colours, halberts, spontoons, filed bedsteads, mattrasses, valances, and all kind of military accouterments and filed equipage.” The listing ends with the assertion that these items were all “ready made” and available “at the lowest prices, as in London.”

This final boast is critical to our understanding of the Colonial import market and why is was profitable for Blanch White’s Upholstery Warehouse to be selling powder horns made on the other side of the Atlantic instead of ones being made right in Philadelphia. By 1759 the Industrial Revolution had already begun in Britain. Cities like London and Bristol were filling up and would soon become over-populated with former agricultural workers who continued to leave the rural regions of England to seek urban employment as semi-skilled laborers. This influx of cheap labor combined with developments in mass production technology meant that the production of goods could be divided into sub-manufacturing trades.

For instance, according the 21 February 1747 issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine [page 101], the trade of the gunsmith in England had, by that time, already been divided into 21 different sub-trades. This high degree of specialization insured that guns were being mass produced very cheaply and efficiently in cities like London and Birmingham. These guns (the vast majority were smooth bored) were being exported to America and sold by import merchants in places like Philadelphia, Boston, or Williamsburg. It is quite possible that the same manner of specialization and cheap manufacturing methods were taking root in the horn working trades as well.

There are a few clues in the literature from that time about the advent of specialization in horn working. According to R. Campbell’s The London Tradesman (published in London, 1747), the Horner is “of Kindred to the Turner, as he turns a great many of the Articles he deals in, which are both numerous and useful.” Campbell has nothing more to say about the items the horners made, but he does add that the horner’s trade is not considered among “the most polite Trades.” He goes on to say that it is “a very useful one, for the stench of the Horn, which they sometimes manufacture with the Heat of the Fire, keeps them from the Hyp, Vapours and Lowness of Spirits, the common malady of England.” In short, it is clear that Campbell did not know much about the horner’s trade. Indeed, the health benefits were all the encouragement that Campbell could give the prospective apprentice other than to say that a journeyman horner could earn “from Twelve to Eighteen Shillings a Week.”

As for his assessment of the turner’s trade, Campbell hints that specialization was well under way by 1747. He wrote that the turners’ trade “is a very ingenious Business and brought to great Perfection in this Kingdom.” He continues that they “differ among themselves according to the materials they use; some turn Wood, others Ivory, Tortoise-Shell, &c, and others Metal, Iron, Brass, Gold or Silver.” He did not mention horn as one of the specialty materials, presumably because he saw the horner as a kind of specialized turner. His essay on turners closes with this statement: “There is an infinite Variety in their Work, and they must be learning all their Life.”

Campbell is less kind to the horn-working comb makers. He wrote that comb maker’s work “neither requires much Labour, Education or Ingenuity,” adding that “It is none of the most profitable Branches to the Master; they earn an honest Subsistence, but though their business is but in few Hands, I never heard of any of them who died remarkably rich.” He notes that a journeyman comb-maker could earn “from Twelve to Fifteen Shillings a Week.” If you recall, a journeyman horner might only expect two more shillings per week. In other words, despite the small number of active comb makers, they could not make a decent living just by making combs. It seems that most types of horners were in the same situation.

The question must be asked then, why were comb makers not diversifying? Perhaps the answer is in their trade name. Is it not possible that comb makers are specialized horner workers who, in response to a growing market, focused on one aspect of the trade? Could it be that generalist horn workers had originally claimed the comb making trade but lost it to those horners who specialized in response to a demand for mass produced cheap horn combs? If this was the case, the evidence seems to indicate that here in America, that sort of specialization was not rewarded in the limited Colonial market.

Returning to the Pennsylvania Gazette, there was at least one American comb maker who was, like many American tradesman during the Colonial era, not limiting himself to one specialty. In the 4 October 1759 Issue, Christopher Anger, “Combmaker,” advertises that he had moved his shop from “Second Street, [at] the Corner of Chestnut Street” to a new location in “Strawberry Alley, within four Doors of Samuel Howell’s Store.” Anger added that customers who visited his new location would “be supplied with all Sorts of Combs, Wholesale and Retail; Also with Powder Horns, and Punch Spoons, &c.” In other words, Anger was a horner who made powder horns, punch spoon and other horns products, but thought of himself as a “Combmaker.” There is even evidence that he considered himself as akin to a turner.

Another key advertisement appears in the 16 February 1764 issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette. It read:

“THOMAS DUNN, Turner, from London, PERFORMS all sorts of Turner’s Work in the Best Manner, in Horn, Ivory, Silver or Brass; he likewise makes Horn Flasks, Butchers Steel Handles, Needle Cases, Nutmeg graters of Horn or Ivory, Horn Pipe Stems, turns Billiard balls, Dice boxes, and Table men, Cane heads, all Sorts of Inkhorns, oval Snuff boxes, Punch ladles, Buttons, curious Flower pots for Ladies, Ivory needles for drawing Ribbons into ladies Caps, horn Tumbler, Shaving brushes, Whip handles of Horn or Wood, &c. Likewise Tortoiseshell Rings made and sold, wholesale or retail, by said Thomas Dunn, at Christopher Anger’s at the Sign of the Comb maker in Strawberry alley, Philadelphia.”

Clearly Anger and Dunn were sharing a workshop and storefront. They are clearly both horners, but Dunn as a turner was specializing at all. Unlike his fellow turners in London whom Campbell described, Dunn was not defining himself as a turner limited to working only with horn. Such specialization was the sure road to financial ruin in America, where skilled craftsmen were fewer in number and where the Industrial Revolution had yet to make inroads.

Now we can return to the imported horns being sold at Blanch White’s Upholstery warehouse, in that same year when Christopher Anger offered his American made powder horns in his shop. Without being able to see these horns and know their prices, so that we can compare them to Anger’s horns, it is impossible to draw any certain conclusions. Even so, if we can believe that the imported horns were being sold cheaper than Anger could sell his, it seems possible that Anger and his fellow American horners were offering items not available on the import market. Could it be that Anger and his fellow tradesmen were offering custom made horns, or even a new American style powder horn that was not made elsewhere? If so, what did this new American style powder horn look like and how was it different from the cheap mass produced horns coming from horn shops in London? Unfortunately I do not have those answers. I look forward to hearing from those of you who think that you might have the answers to these questions.

A Most Ancient Art & Mystery

July 15, 2011 by Bill Carter

Filed under Articles from the Archives

The following article by Tom Ames was first published in the December 1996 issue of The Horn Book. You’ll find that a lot of Tom’s feelings, attitudes and beliefs mentioned in this article are also reflected in the segment “Part II – Judging Accouterments at Dixon’s” in the Winter 2011 issue of The Horn Book. This discussion of “the inner voice” and “our quest for understanding” the true meaning of our heritage through various artifacts is always of great interest.

Our thanks to Tom for allowing the reprint of this article on the Website.

-Bill Carter

A Most Ancient Art & Mystery

by Thomas E. Ames

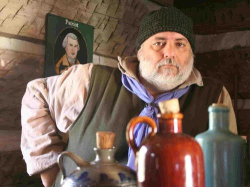

Thomas Ames

Often the most rewarding experiences come when we least expect them: from unexpected finds in flea markets to an all too rare horn at a good price (for the buyer, that is) at a gun show. I call these “gifts of the spirit,” almost as if the one who had lived with the relic horn or gun reaches into our subconscious to prepare us for the discovery. A few of you may know the story behind how I came to find a spout stopper that seemed to have gone with a horn purchased on a bag half an hour earlier. The original stopper with a vent pick inserted in the shaft had been lost from the original outfit. Within the hour, some miles distant, a stopper complete with pick was found.

Coincidence? No, such events occur far too often for it to be chance. How many people know the story of how Madison Grant came to reintroduce the folding Barlow pattern knife and fork pictured in The Kentucky Rifle Hunting Pouch? [plate 128, page 197] Was this an original set? Perhaps, perhaps not. But each exemplifies the character of the other and by that compliment they encourage appreciation and our quest for understanding the lives of our forebears. Such is the value of the relics they’ve left behind for us. Listen and feel of what they tell us and listen to that inner voice as you recreate them.

Such is the value of the work we leave behind as contemporary artisans following in the footsteps of our ancestral heritage. At times even the plainer examples of our labor become masterpieces by virtue of their voice to our inner being. Sometimes they radiate their own specialness beyond even the critical eye of their maker.

Bob Chattin, a well known horner in southeastern Pennsylvania and a founding member of our Company, has been active for many years at Dixon’s Gun Fair. Early on, I chose to establish a working friendship with Bob and his partner, Jeff Renninger, because they were competent craftsmen in their own right. Both Bob and Jeff worked in a traditional manner and that was all important to me. They did not need my influence beyond the critique stage. They deserved the right to develop in their own way, their own unique style.

Well, things change over the years and we became more than passing acquaintances at the Gunmakers’ Fair each year. Yes, I wanted an example of the work they exhibited and quietly waited for that special piece that would encompass a regional feeling as well as fill a void for pouch service related to a particular gun.

I found that special piece at the rifle frolic on the Henry Factory site last June: a ringed or banded horn of fine architecture, painted red, shadowing an original regional production. It would serve to balance the refined architecture of the plain rifle of the region that I use in the field.

In July, Bob Chattin approached me as I arrived at the Gunmakers’ Fair at Dixon’s and handed me a small pocket horn. On it he had engraved a likeness of the regional liberty capped figure head. He asked me to critique the likeness.

Many of you know of my long research about this particular motif so I didn’t consider Bob’s request as anything more that an honest appraisal. The first thing to strike me, however, was the well polished honey colored maple base; semi-domed, it radiated a degree of depth that struck me as a very fine attribute to the entire package. It was like looking into a clear sun lit pool of water with each layer of grain reflecting its own light. I commented to Bob briefly on the whole horn and made note of the attraction of the base treatment.

Late on Sunday afternoon, Bob brought the horn to me again and noted that perhaps I’d not seen everything the first time. As I rolled the horn around, I was pleased and honored to see a newly made inscription: “To Thos Ames, a token of respect and friendship from Robt Chattin.”

On my way homeward from Dixon’s, I stopped for dinner with the Odle family. I related the story of Bob’s presentation and handed the horn to him. Mark was drawn to the base details as we sat across the dinner table. In the restaurant’s lighting, a face appeared to radiate from deep within the base plug!

There, in the maple, was the liberty capped figure head of Tammany appearing to stare from the natural holograph. Intentional? I think not! Each fiber of wood grain picked up by the artificial lighting in the restaurant could not belie the unintended spirit behind its maker. No creative hand could have represented the spirit of Tammany any better. It was dimensional, the face reflected in the holograph of creation. The dictionary defines holograph as “a document solely in the handwriting of its author.”

When I turn the base upside down, as with any two faced grotesque, another face appears to issue from its depths – that of a wizened old man. Eyes drawn, his face lined and creased with knowledge, his mouth hidden behind a drooping mustache. I have to ask myself: who is the author of such a document? Who are we to judge the true creative spirit of another? Why do we feel we must compare the merits of one against another? What value do we place on our special gifts, be it a contemporary horn with special meaning or a relic that somehow found its way to us in a manner that defies rational explanation? And finally – Bob, did you know?

I trust we all shall find our answers as we continue to express ourselves through creative spirit and the knowledge of the phrase that so endeared itself to the crafts of old as “the ancient arts and mysteries” will be made known unto you.

Heating Cow Horn by The Horn Swogglers

August 31, 2010 by Bill Carter

Filed under Articles from the Archives

The article selected from the archives for this segment is from the February 2005 issue entitled “Heating Cow Horn” by the Horn Swogglers. I have no idea who the “Horn Swogglers” were, but they employed a rather humorous approach to the age old question concerning the heating of horn.

This article also ties in nicely with Willy Frankfort’s article on the “Horn Kiln” which will be in the September 2010 issue of The Horn Book.

-Bill Carter

Heating Cow Horn

By The Horn Swogglers

For those of you who have experienced the frustration of inaccurate information about how to work horn and thus have been horn-swoggled, this column will help ease your agitation and set the record straight. It’s written by the most knowledgeable, but not necessarily humble, horn workers in the world, and based on the most current information from NASA, spanning the entire galaxy. Here we will answer the perplexing questions that HCH members have about the horner’s craft. So, if you’ve ever been horn-swoggled, that is, bamboozled, befuddled, or bewildered, about working horn, send your inquiries to The Horn Book Editor, our very own Lee Larkin (known in some circles as “Lurkin” Larkin, for reasons we will not go into here), via email or snail-mail, and he will forward each and every one of them on to us. This prevents the U.S. Postal Service from having to create an entire new zip code for yours truly, the Horn Swogglers, and also gives Lee something to do.

Our first question, picked at random from the stack of mail we keep tripping over on the shop floor, has to do with “correctly heating horn.” The “burning” question is, “What is the correct way to heat horn?”

Now, this may seem a little round-about, so just bear with us here. Picture yourself in the “Horner’s Game Show,” trying to choose the door that is hiding the correct answer. How would you choose the right door? We asked that great horn-swoggler Jack Horner, sitting over in the corner of our shop, and he said, “You could try sniffing each door.” From our experience though, the human nose only tells the brain, “Something stinks – get out of here,” and then, after approximately 96 seconds, you can’t distinguish smells very well anymore. So, if you sniff too long at any one door, it will all start smelling the same real fast. On top of that, horn heated “wet or dry” has different odors, so smelling the doors is a very limited option. After further speculation and debate, we threw up our hands, and decided to just start at door number one – forget the grand prize.

Behind door number one we found Mr. Ronny Horner. He’s heard all about horning from his rendezvous buds who tell him that you just need to boil the horn in water to soften it. The reason Ronny is behind door number one is because it is attached to his dog house, which is his current postal address. Ronny tried boiling horn on the kitchen stove. He boiled and boiled and boiled his horn, and forgot that Mrs. Ronny Horner was bringing the “Power Through Prayer” ladies group over for ice cream. Too bad for Ronny! After all that, we’ve heard on good authority that Ronny’s horn was still not soft enough to be worked, and that Ronny’s olfactory senses are now gone. But he still has eyes and ears, so we’ll make this real plain for him: boiling horn in water was never, is never, and never will be, the correct way to heat horn hot enough to work it so that the horn retains its strength and looses its original memory. Well, maybe we should move on to door number two.

Behind door number two is Hairy Horner. Hairy’s name is an acronym of the technique he uses – hot air. Hairy knows that horn has to be heating greater than what Ronny could get with boiling water and has decided to pull out his old paint stripping hot air gun. Unfortunately, Hairy stripped so many houses in the neighborhood with his hot air gun that the fumes from the lead based paint seem to have already turned Hairy a little airy. Actually, the gun gets the horn hot enough, but because of the air flow, it dries and dehydrates the horn too quickly, and the horn scorches and melts rather that becoming plastic. Notice also that Hairy’s door is connected to his garage which is connected to the kitchen. Hairy thinks that Mrs. Hairy Horner won’t mind the smell in the garage. It just goes to show how much affect lead oxide has on the brain, has on the brain. We should continue our search and look behind door number three.

“Holy Cow!” Mic Horner’s shop or “lab” looks like something from “Nightmare Before Christmas.” You might think because of his name that Mic is descended from ancient Celtic horners, but you would be mistaken. Mic’s name actually comes from his heat source – the “Mic”rowave oven. Notice also that door number three is actually the kitchen door. Mic hasn’t learned a thing from the sad experiences of Ronny or Hairy. Or, to quote a great American hero, ‘Stupid is as stupid does.” Mic’s horn is frizzled beyond use. Frizzled is his middle name and frazzled are his nerves. Putting horn into a microwave is like putting your finger in a hot light socket. Mic even tried the defrost and popcorn settings, but to no avail. Poor Mic will be heating his TV dinners on the steam vent near the city rescue mission this winter and his wife will be filing for P.F.A. All you aspiring horners should take note, and “fear and shudder.”

And, finally, we come to door number four (bet you thought there were only three doors in this horner’s game). Well, behind door number four, we find Hap Horner. Hap’s name is no mistake. He’s a happy horner. It just so happens that Hap heard about the HCH and hastily joined before he haplessly made all of the above horrible errors. Hap’s door actually leads to a real shop that is not attached in any way to his house. To use dry heat, Hap has set up a grill outside of his shop where he can heat his horn over a fire. Otherwise, he uses an electric hot plate in his shop. He also has an oven in his shop to bake horn. For wet heat, Hap has an old pot or turkey fryer full of lard. Hap still has most of his brain and olfactory functions. Not only that, but, you guessed it, Hap is still happily married. The grill, oven and fryer are not the baubles of a divorce settlement, but were consented to by Mrs. Hap Horner, so they could live in health, harmony, and happiness. Pretty smart, huh?

Whether by the grill, which takes a practiced eye, or by the oven, which takes a 300 degree setting, or by the fryer, at no more that 320 degrees of wet heating, the goal is to make a piece of horn plastic so that when it cools it will not loose its strength, but will loose the memory of its old shape and permanently retain the memory of the new shape. The only time a horn should be boiled is when the bone core is separated from the horn after the horn is removed from the cow (we strongly recommend doing this 1.) after the cow is dead, and 2.) outside!). And, so, a deep, dark mystery of the horn trade is answered by the indubitable Horn Swogglers. To quote another great American, “Shazam!” ᾨ

Griffins or Hellhorses? by Billy Griner (from the February 2006 issue of The Horn Book)

July 12, 2010 by Bill Carter

Filed under Articles from the Archives

In preparation for Dixon’s, I was updating the inventory on past issues of The Horn Book and couldn’t help but peruse some of the old issues and realized, once again, that there are a plethora of articles that have some invaluable research. So I decided to change “The Horn Book Feature Article of the Month” to “Articles from the Archives” in hopes of generating more interest in past issues. To start this new segment I selected an article from the February 2006 issue entitled “Griffins or Hellhorses?” by Billy Griner. I hope you will enjoy this new segment. –Bill Carter

By the way, here is the link to purchase past issues of The Horn Book. >>Past Issues.

Griffins or Hellhorses?

By Billy Griner

Magical, mystical creatures are relatively commonplace as engravings on antique powder horns. It is not unusual to find a mermaid or fanciful serpent engraved alongside ships or even an angel tucked into the border work of an engraved powder horn. The list of magical creatures that came out of the imaginations of our forefathers is not long, but I believe these creatures are meaningful, because they reveal something of the spirit of the age.

One such mystical creature that shows up from time to time is what some have termed a “griffin.” This “griffin” does not appear on many antique horns. There are only eight known to exist. Two men are believed to have engraved all of them during the French and Indian War, between 1759-1761.

One look through Jim Dressler’s fine book, The Engraved Powder Horn, reveals illustrations of four different horns with what he and others have called a “griffin” engraved on them.

That “griffin” has puzzled me for some time. While looking at engraved features on other horns, there was no doubt what they were: unicorns looked like unicorns, angels looked like angels, and lions looked like lions. So why didn’t these “griffins” look like a griffin to me? A traditional griffin is half eagle and half lion. But the creatures that caught my attention looked more like a half dragon and half horse. I’m sorry, but it just did not look like a griffin to me at all.

It’s interesting how we connect the dots sometimes. I was reading one of my kid’s books from the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling and stumbled across a creature that she called a thestral. Her description of this creature instantly reminded me of the “griffin” on these old powder horns.

Rowling is known for using only creatures researched from mythology in her books. So, I began a lengthy search trying to tie down information concerning what Rowling called a thestral. I found that the word thestral is a twentieth century term used by science fiction and fantasy writers for a creature originally known as a hellhorse, demonsteed, or nytmare. These names come from a much older source – ancient Greek and Roman mythology.

In Greek mythology, hellhorses drew the chariot of Haides, the god of the underworld. In ancient Rome they were called Plutonian Demonsteeds, where they pulled the chariot of Pluto. Fire breathing steeds also drew the chariots of Ares (Greek) and Mars (Roman), the gods of war. Both the gods of war and the god of the underworld are associated with not only war and death, but also plague, pestilence, and fear. That the ancients viewed these steeds with awe and fear is a testament by the names they were given: “Murderous Ares came (to the battlefields of Troy)…Aithon (Red-Fire) and Phologeus (Flame), Konabos (Tumult) and Phobos (Panic-fear), his car-steeds, bare him down into the fight, the coursers which to roaring Boreas grim-eyed Erinnys bare, coursers that breathed life-blasting flame: groaned all shivering the air, as battleward they sped” (Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 8.239). The Romans called the horses of Mars “lovis Terrorque Pavorque…Fear and Dread (Valerius Flaccus, Ar. 3.89). Haides rode in his golden chariot drawn by the four hellhorses when he inflicted Thebes with plague as punishment for not allowing the burial of the dead warriors of the Army of the Seven against Thebes. Haides was also called “Plouton, master of the black-winged Oneiroi (dreams) by the Greeks.

So, what exactly is a hellhorse? A hellhorse is a member of the same group of mystical creatures that the Pegasus belongs to: That being winged horses or pegasui. But, of course, a hellhorse is no friendly Pegasus. According to Rich’s Pegopedia (a web site concerning winged horses throughout legend and myth) hellhorses are creatures “having the basic form of a horse, but are really more reptilian by nature. They have a sleek black/purple scaly hide, cloven hooves, a barbed tail like a dragon’s and a beaked snout, the forked tongue of a serpent, and tresses of fire for their mane, fetlocks and tail, and the ability to spit fire from their mouth. Hellhorses have the ability to fly, but not all require the addition of leathery winged appendages, like those of a bat, to do so.” Roughly the same description appears in several other bestiaries of mythological creatures on the internet.

In comparison, here are the shared features of the creature engraved by Cresey and the A. Cleveland – J. Carril carvers: the basic form is that of a horse with a scaly hide (rows of dots on the creature), cloven hooves, a barbed tail, and a forked tongue; they seem to be spitting fire, and of course they have wings for flight.

So, here is where I think the hellhorse connects with the eighteenth century colonial American mind. The engravers of these horns lived in a time where a classical education was normal. This included a significant exposure to Greek and Roman mythology in their studies. In fact, it was common to be tested on the mythology of the Greeks and Romans in order to gain admittance to colleges like Yale and Harvard. The horn carvers of the mid-eighteenth century were exposed directly or indirectly to the mythology of the Greek and Roman world. So the idea that an eighteenth century engraver would have known what a hellhorse was and what it represented is completely plausible.

Needless to say, the men who carried these horns were all survivors of war and pestilence. Easily the greatest killer of soldiers at Ft. Edward at that point in the war was smallpox. All of the original owners of the horns survived this “plague.” Could it be possible that the engravers were pointing out that the owners of these horns had lived through the hellish nightmare that was the outbreak of smallpox at Ft. Edward and Crown Point? Or could the figures have been engraved because these men had seen the horrific face of war? Had they metaphorically seen the god of war sweep over the field in his chariot being pulled by his murderous hellhorses, spreading death, fear, panic, and tumult, as well as plague and pestilence in his wake? All of the emotions of war seem to be represented by the hellhorse, demonstead, and nytemare.

While there is no direct reference that would say that the hellhorse as engraved on these powder horns represents anything more than the fancy of the engraver, to my mind, for the hellhorse to appear on all of these horns, a purpose for their repeated presence is demanded. I believe that the engravers of these horns carved the hellhorse on them as a reminder that each of these men had seen the nightmare of war and been very close to death, having witnessed the plague of small pox first hand, and lived.

Now, more than ever, I am confronted with one simple question. Just how much of what we see engraved on these antique powder horns has a meaning to the original owner that is lost on us? Our demythologized and secularized twenty-first century culture no longer places an emphasis on remembering Greek and Roman mythology, so most of us don’t. The hellhorse is a reminder, good or bad, of how far we have distanced ourselves from the mid-eighteenth century colonial American mind. ᾨ

Willy Frankfort’s 1 of 1000 Powder Horn (from the May 2009 issue of The Horn Book)

June 11, 2010 by Bill Carter

Filed under Articles from the Archives

In 2009, Willy Frankfort represented our Guild and took on the task of producing the 1 of 1000 Powder Horn for the NMLRA Endowment Program. I asked Willy to take photos of the horn from start to finish for a “Photo Journal” so all members could see how his work progressed.

In 2009, Willy Frankfort represented our Guild and took on the task of producing the 1 of 1000 Powder Horn for the NMLRA Endowment Program. I asked Willy to take photos of the horn from start to finish for a “Photo Journal” so all members could see how his work progressed.

[for the complete article, click here…]

The Screw Tip Powder Horn (The Horn Book – Feb 2007 edition)

May 3, 2010 by Bill Carter

Filed under Articles from the Archives

The Horn Book is the official publication of the HCH; it is published three times per year. It features pertinent information about the HCH, its members, and all kinds of horn objects. The following is an article from the February 2007 edition by Roland Cadle & Art DeCamp.

An American Legacy: The Screw-Tip Powder Horn

The screw-tip powder horn is as uniquely American as the

famous Kentucky long rifle with its hinged, brass patch box.

By Roland Cadle & Art DeCamp

The American screw-tip powder horn was an innovation by professional horners, turners, and a few rifle makers. With production centered in Eastern Pennsylvania in its earliest years, the screw tip horn thread its way South on the great wagon road, west through the Cumberland Gap and across Forbes Road and down the Ohio River, thus paralleling both the production and migration of the rifle it served. Our most respected “rifleman” scholar craftsman, Wallace Gussler, often illustrates these points while wearing a hand-made, linen rifleman’s shirt and carrying an American rifle, pouch and Pennsylvania screw-tip horn, each item the earliest known American type. Turned ends and threaded, removable tips, dating to the 17th Century, can be found both in England and on the European continent. So, in what way is this ancient technology uniquely American? Simply put, it is the application of a screw on tip, or screw-tip, on an otherwise naturally shaped cow horn. In Europe, this was not done on powder horns because quantity was not needed and the natural shape of the horn was modified to show the application of the “mystery and art” of the horner’s craft. So, let’s look at the American Screw-Tip… During the French and Indian War, the Colonies were divided into Northern and Southern districts.The Southern district included Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland,Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. The screw-tip is a product of the Southern district. At least three horners, located half a block from the wharfs of Philadelphia in Strawberry Alley, advertised “the finest powder horns” for sale during the French and Indian War. As early as 1759, one horner named Christopher Anger advertised “The finest American Made powder horns, combs, spoons, etc. at the sign of The Golden Powder Horn and Comb.”We believe the screw-tip powder horn originates in one of these shops.

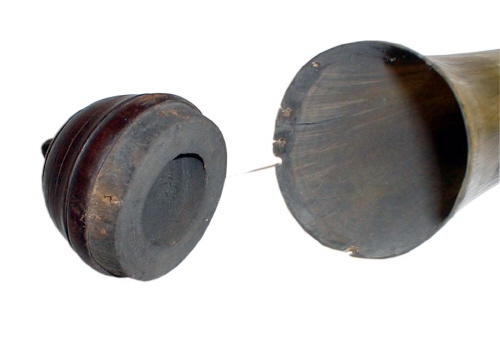

Screw-tip horns come in two distinct types.The tip either screws off (external) or screws in (internal). The earliest known screw-tips are internal with an applied collar to reinforce the threads, coming from Southeast Pennsylvania Dateable external types are currently traceable to the mid 1770’s. Before we give a school and region overview, let’s answer the obvious question: “Why a Screw-Tip?”

Various writers have dealt with the removable turned horn tip as strictly a utilitarian device – remove the tip and it facilitates refilling the horn by serving as a funnel (external screw tip) or leaving a bigger hole (internal screw tip) to allow quicker refill with a funnel. Since all horns are refilled by funneling the powder into the horn, it seems a prodigious amount of work just to cut twenty-six seconds off the refill time. Rather, we believe the size of the screw hole was more a happy byproduct of the production process in the quest for speed. Mechanically speaking, the screw tip allows for division of labor within a shop (an 18th Century factory concept), thus allowing several operations on the same horn nearly simultaneously. Turner One swages the hot horn onto a mandrel, turns the base of the horn true, and adds any integral molding (the double lines or surface bead of a York County horn).Turner Two takes the diameter of the horn base and turns a plug to fit. Using a tap inserted into the tip of the horn,Turner Three either tapers the end for an applied collar (internal screw tip) or shoulders or chases a set of threads (external screw tip).Turner Four can turn the respective screw tip, and then all of the parts go to the finishing room where the horn is scraped, polished, dyed or decorated and assembled. As late as 1840 records show two shops in Lancaster, Pennsylvania producing almost 20,000 horns a year using this basic method.

External Screwtip

Internal Screwtip

Concave Berks Plug

These are some general observations about the screw-tip powder horn, but a picture is worth a thousand words. This article presents information and photos of six distinct screw-tip horn varieties that seem to turn up most frequently within Pennsylvania.These are the most commonly seen varieties even though, through collecting and observing original powder horns, there may be as many as twelve different “schools” within Pennsylvania, made in at least eighteen different shops. Each of the six known “schools” is presented hereafter in approximate chronological sequence.

Early Philadelphia Horns (Circa 1750’s to 1780’s)

Early Philadelphia horns have a high domed hardwood base plug (usually maple) with a wide over hanging edge next to the horn and a concave “wasp’s waist” just above the bead. Like most other screw-tip varieties, the base plug is hollowed out on the lathe to help prevent checking. Frequently, there is a turned horn, or metal band at the base end of the horn.Wire staples are used for attaching the carrying strap at the spout and base end.The staple in the base can be staked like a staple with two legs, or is often bent into a loop, twisted, and inserted through a hole in the center of the plug, and clinched over on the inside.There is always a heavy applied collar on the mouth of the horn, used to reinforce the internal threads, that often appears larger in diameter at the spout end than at the back end.The screw-tip itself is of the internal type and is generally turned in the shape of a chess pawn.

PHILADELPHIA HORN

Berks County Horns (Circa 1790 to 1820)

There are at least four different shops that made the “Berks” style horn which is characterized by the oblong wooden base plug with an integrally turned button for attaching the carry strap.The screw-tip is of the internal variety, with an applied collar at the spout to reinforce the internal threads. The base plug is always turned with an undercut at the overhang where it joins the horn such that the edge of the horn is actually captured by the wooden plug.

BERKS COUNTY HORN

Lancaster Horns (Circa 1770 to 1890)

Lancaster horns are possibly the most common variety having been made in Lancaster for at least 120 years, by at least four different shops. This is the first of the external screw-tip styles. Many Lancaster horns have the low dome, flat base plug with impressed “rope” on the top of the plug. Staples are used at both ends for strap attachment. The elongated, gracefully turned screw-tip features external threads. Even though this style was made for such a long period, the basic form of the design did not vary greatly over the course of time.

LANCASTER COUNTY HORN

York Horns (Circa 1775 to 1830)

York horns are similar to the Lancaster type in that they have external screw tips. York horns, however, are much more highly developed from a design, fit and finish, and aesthetic perspective.York horns utilize fruitwood such as apple, pear, and cherry for their plugs, which are turned concave inside.The “classic”York horns have the high dome base plug with chip and rope carving.The external screwtips are turned in a finer manner with more decorative flair, usually featuring a number of grooves and raised beads. A pair of concentric grooves, forming a bead, are cut at both the base and spout ends of the body of the horn.

YORK COUNTY HORN

Franklin Horns (Circa 1790 to 1820)

Franklin County horns are external screw-tip horns with great similarity to York horns. Key differences are their almost flat, low domed base plugs and a set of three concentric grooves forming a double bead, turned in the base of the horn. The screw-tips are generally shorter than York horns, and feature a wide base end and very thin spout.

FRANKLIN COUNTY HORN

Centre Horns (Circa 1798 to 1845)

Family members originally trained in York, PA made Centre County horns. Thus they are of similar construction, but much more simple in actual execution. They feature a domed wooden base plug with an iron staple for the strap attachment and a squared staple at the neck for a front strap attachment. There is a single decorative bead turned on the base plug next to where it contacts the horn. The external screw-tip is simple, with a beehive type turning at its base. In conclusion, the distinct threaded, turned tip and turned base plug became the signature of the Pennsylvania screwtip horn and reflected the shop or region from which it came. These professional, shop-made powder horns are truly unique American relics. New examples of these horns continue to surface and undoubtedly will adjust our understanding of where and who made them.

CENTRE COUNTY HORN